A Path for Power

Cloudcroft Tunnel eases access to electric services

By Florence Dean

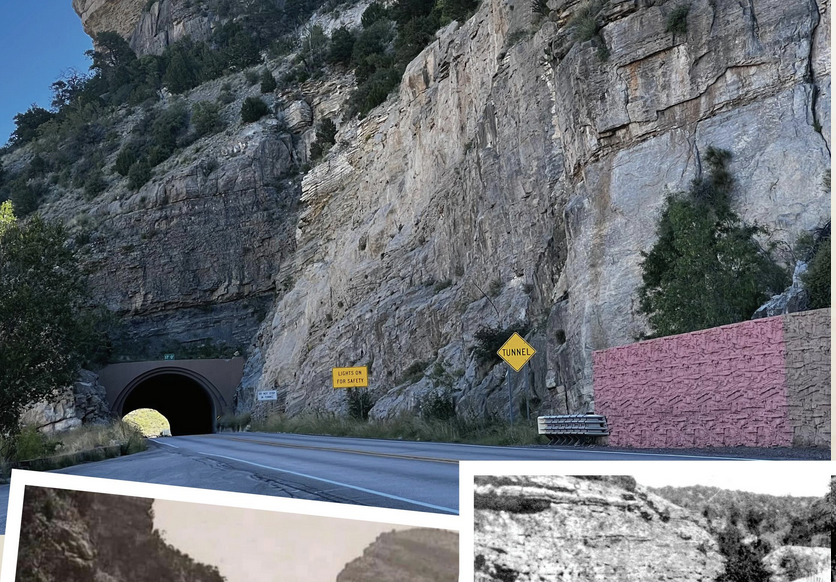

Only one active highway tunnel is in use in New Mexico: the Cloudcroft Tunnel on U.S. Highway 82. It is subject to blockage from rockslides and falling trees from time to time.

During a slide, traffic backs up into High Rolls and drivers get out of their cars to visit. Some folks backtrack into High Rolls and take the mostly dirt road through Fresnal Canyon into Alamogordo. This road is passable for cars and the occasional ambulance, but big trucks have to wait.

Those who routinely travel U.S. 82 watch for rockslides while appreciating the convenience this road provides. For Otero County Electric Cooperative, which provides power in the area, it is an essential tool.

“The tunnel, along with the rest of Highway 82, is critical for OCEC to provide reliable electric service to Cloudcroft and the rest of the Southern Sacramento Mountains,” OCEC CEO and General Manager Mario Romero says.

The Cloudcroft Tunnel is a vital part of what was originally known as Highway 83. Its necessity was recognized by local leaders as early as 1932. At the time, the journey from Alamogordo to Artesia required passing a treacherous mountain trail, dusty and twisting through the Sacremento mountains. In 1939, a delegation from Alamogordo, Tularosa and Cloudcroft met in Santa Fe to request construction of Highway 83 from Artesia to Alamogordo.

It would be another decade before that road was built. Construction began in 1947. The project cost $2 million, including the 528-foot-long and 34-foot-wide tunnel. It was said to be one of the heaviest and most expensive sections of highway ever built in New Mexico. The road snaked through Bailey Canyon from Toboggan—where the railroad sometimes stored trains—to Cloudcroft and down the mountain, through the tunnel to Alamogordo. It was specified that no section of the road would have more than a 6% grade.

Construction involved cutting off a portion of a cave above the road where Native American artifacts were found. Water still runs down the side of the mountain here. In the winter, it freezes into an icy sculpture.

Dynamite used during the tunnel’s construction created fractures in the cave’s roof and walls, requiring workers to use more concrete than planned and narrowing the tunnel.

The tunnel opened Sunday, Nov. 20, 1949, with a gala attended by 1,000 people.

Over the decades, the tunnel has been rehabilitated and reinforced. Rockslides occur east and west of the tunnel, sometimes major, occasionally small enough to damage a vehicle but not close the road.

Many of OCEC’s employees pass through the tunnel on their way to work, and the co-op frequently uses it to move equipment from its main yard and warehouses in Tularosa into the field throughout its service territory.

“The tunnel is something we don’t spend too much time thinking about, but when it is blocked, it causes a lot of inconvenience, longer outages and increases costs for our entire membership,” Mario says.